![]()

Introduction: The significance of Industry and Idleness

In 1747, William

Hogarth, the engraver, created the famous moral series Industry and Idleness which he said was "calculated for the use and instruction

of youth." . This series aimed at a public of apprentices which

Hogarth knew very well, having been an apprentice himself, and being

a governor of the Foundling Hospital which had been built in order

to have the foundlings apprenticed. Thus, as opposed to very sophisticated

series such as Marriage a

la Mode (1743) or progresses

like A Harlot's Progress (1731) or The

Rake's Progress (1733-34),

which aimed at an educated public, Industry

and Idleness has a more immediate,

pointed meaning. As a matter-of-fact, Hogarth wanted this particular

series to be more affordable to less wealthy people and especially

the apprentices’ masters who could then hang the prints in their

workshops as an example of the right way to behave. Referring to

that particular point, in the art section of the Evening Standard,

concerning the Tate Gallery exhibition for Hogarth's tercentenary,

Brian Sewell says : "If, in the Renaissance, the paintings

that embellished churches were the Bible of the illiterate poor,

then in 18th century England Hogarth's engravings were powerful

political and social propaganda for those who could not read, as

well as those who could." . Hence, in order to make the engravings

cheaper, Hogarth is said to have left aside all the intricate engraved

devices, tricks and details he usually resorted to - those details

that made of him more than a mere engraver.

However, this series

is more subtle than it seems at first sight. Therefore, it is crucial

to look at the two apprentices' story by studying the different

graphic references and codes that the artist has slyly inserted

within the plates. As a matter-of-fact, this study can show us interesting

facts about contemporary society. It can tell us a lot about eighteenth-century

manners and aspects of life and, above all, about the intended moral

meaning of the plates. Then, we’ll move to a potentially deeper

analysis where we shall try to find out more about the artist himself.

We'll try and see how his own desires have taken part in an alternative

reading of the series in which the values depicted within the initial

moral reading can be challenged and thus reveal the hidden discourse

of Industry and Idleness.

PART I

An iconological Reading of Industry and Idleness |

Before starting

the study of the different plates, there is a very important fact

to bear in mind. When Hogarth engraved moral series, or prints depicting

London life and people, he knew that his work had a very high dramatic

value. Eighteenth-century people would not see the prints just as

pictures nice to look at, yet remote from what they lived, but on

the contrary they saw them as violent and very often disturbing

projections of their own reality. Thus, for instance, when Sir John

Soane the architect, acquired The

Rake's Progress (1733-34),

he decided to hide it behind some sort of massive inside shutters

so that children could not see the pictures and because he, himself,

could not stand the sight of such a violent depiction of everyday

life...

The first plate of Industry and

Idleness shows the obvious

point of the whole work very clearly. Each apprentice is working

at his loom. On the right-hand side of the engraving, stands Francis

Goodchild the industrious apprentice. On his face the keen concentration

on the work he is doing can be seen, and a faint smile on his lips

shows the pleasure he is getting from it. On the floor near his

loom there is a little book entitled "The Prentices Guide".

This book was often offered to boys when they signed their indenture.

In it, they could read warnings against running away, and basic

moral lessons on how they should behave towards their masters and

their work. This book is a clue on how willing he is to learn. The

window which is in the centre of the engraving spreads the light

of day on him as if to attract the reader's eyes on this character.

On the contrary, on the left-hand side of the engraving Tom Idle

stands in the shade. The same "apprentice's guide" that

is lying next to Goodchild's loom can be seen at Idle's feet. But

in what a state! It is torn apart. The boy has probably let the

cat sharpen its claws on it. The expression on Idle's face is totally

different from that of Goodchild. He seems to be yawning either

with tiredness or boredom, or maybe is trying to see how the loom

is working. Above the industrious apprentice's head, on the wall

behind his loom, there is a ballad called "Whittington Ld Mayor"

which is a reference to Dick Whittington, an historical figure,

who had been Lord Mayor of London three times in Medieval times

(1397, 1406 and 1419). The legend tells us that, as an apprentice,

Whittington was running away from London when he thought he heard

the bells ring "Turn again Whittington, Lord Mayor of London".

It also tells us that his fortune was made when his cat, sent abroad

on a merchant's ship, killed so many rats that the king of Barbary

bought the animal for a large amount of money. The reference to

this popular pantomime character tells us much about the future

Hogarth has reserved to the industrious Goodchild and about the

model the latter has chosen to follow. This story is also an important

element of the hidden discourse of the series, so we have to keep

it in mind.

As opposed to this, the future of Tom is far

more uncertain. Above his head, not on a solid wall but on the wooden

structure of the loom, a piece of paper is stuck. It is the ballad

of "Moll Flanders". Here Hogarth makes an allusion to

the novel written by Daniel Defoe in the form of a confessional

autobiography. It is important to notice, for later in the study,

that the full title of Defoe's book is The Fortunes and Missfortunes

of the Famous Moll Flanders Who Was Born in Newgate and During a

Life of Continued Variety of Threescore Years Besides her Childhood,

was Twelve Year a Whore, Five Times a Wife, Twelve Year a Thief,

Eight Year a Transported Felon in Virginia, at Last Grew Rich, Lived

Honest and Died a Penitent. Moll, the supposed author, was born

in Newgate jail and she has fluctuating fortunes through her marriages

and affairs, with prolonged periods in the London underworld and

in the plantations of Virginia where her mother had been transported

. In front of Tom, there is also a huge beer tankard - a good hint

concerning his morals - on which the following words are written:

"Spittle Fields". This tankard was placed here by Hogarth

less to allow Idle to drink than to associate him with Spitalfields,

an area to the east of the City, famous in the late seventeenth

century and in the eighteenth century for the manufacture of silk.

In fact, "By the 1720s Spitalfields had become, with Lyons

and Nanking, one of the great silk centres of the world." .

An important element in the success of the factories was the skill

of the immigrant Huguenot weavers who started to immigrate into

England after the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. But

this place was very poor, much like a "ghetto" according

to Roy Porter. Near Tom, attached to his loom, a smoking pipe can

also be seen. Thus his models are Moll Flanders, beer and tobacco,

all of which is not likely to please the third character on this

plate, situated on the right-hand side, the two apprentices' master,

Mr West. On this plate, he can be seen throwing angry stares at

Tom while holding a cane, as if threatening the idle apprentice.

Actually, masters were allowed to beat the apprentices - fortunately

not to the point of causing death, even if this happened from time

to time - as they were supposed to teach them discipline as well

as a skill. So, apprentices were very often given the cane as a

punishment. And that is a reason why many of them would run away.

On the printed frame, two other sets of clues tell us about Idle's

and Goodchild's respective fates. The first hints are graphic devices.

On the top right-hand side, prolonging the master's stick, there

is a kind of sceptre, a mace, the symbol of power. This mace, in

particular, is that of the City of London. There is also an alderman's

gold chain hanging from the mace and next to it, the sword of state.

But, on the top left-hand side, there are ropes, a whip and some

sorts of manacles, fetters. The second set of hints are the proverbs,

quoted from The Proverbs in the Old Testament, written on the printed

frame under each character (they appear all along the series associated

with quotes from the Bible).

Thus, in this first plate Hogarth obviously puts the idea of opposition

and contrast in the centre. Indeed the codes are easy enough to

decrypt the message Hogarth wanted to put through. In fact, Plate 1 could have been a whole in itself if the

artist had only wanted to show that, when apprenticed, hard work

is the way to success. But there is more than that to it, more than

meets the eye. Thus, in the following plates, the opposition between

the example to follow and the one to avoid, personified by the two

apprentices, is still there and central though it is not shown on

the picture since, from now on, the characters follow two different

paths in life. Even though one's life makes a whole and hence cannot

be opposed or even compared to anyone else's, as far as the simple

notion of one's own choices is concerned, for practical purposes

and because Hogarth has alternated Goodchild and Idle's stories,

the following plates can be studied in pairs as follows (2/3) (4/5)

(6/7) (8/9) and (11/12). Number 10 has to be studied separately

as Idle and Goodchild are once again reunited on the same engraving.

The

setting of Plate 2

is a church. Some critics say that it is St Martin-in-the-Fields

as it is a City church that architecturally speaking looks most

like it. However, the proper name of the church is of small importance

as Hogarth's title for this engraving is "The Industrious'

prentice performing the duty of a Christian". The stress is

on the action, "performing", and the point of this plate

seems to be all there in its title. This takes even more meaning

if we give a look at Plate 3. As opposed to the other apprentice Idle doesn't attend

the service, he does not perform his "duty". Now, in itself,

this would be of little importance if Hogarth had not added signs

of fate and destiny on the two plates, with a moral purpose. Hence,

if we move back to Plate 2,

we see that Goodchild, once again in the light, is with a girl who

in fact is his master's daughter. They are singing from the same

psalm book. The fact that this happens in a church is quite symbolic

of what to expect for the couple. Another safe choice for Goodchild

as, at that time, an apprentice who married his master's daughter

was on the right way to inheriting the business. While Francis is

"performing" his duty, Idle is "Playing in the Church

Yard" with three pickpockets (on the finished drawing for this

plate, the title is "the bad 'prentice at play in the churchyard

with Pickpockets." which Hogarth has replaced on the print

by the verse from the Proverbs). The setting is obviously linked

to his fate. Hogarth draws the viewer's attention to a selection

of human skulls and bones emerging from the ground all along the

coffin Idle is lying on. There is also an open grave, a symbol which

tells us that below Idle there is Hell, wide open and waiting for

him. Behind him stands an irate churchwarden with upraised cane,

ready to use his instrument of correction on the boy who is gambling

on the Sabbath. Hogarth is still playing with symbols on the printed

frame - a mace and a halter - in order to give hints about the eventual

ends of Goodchild and Idle. However, at this point, we can notice

that the way these symbols are placed on the frame is not apparently

logical. Indeed, on Plate1,

the fetters and whips were on Idle's side and the mace was on Goodchild's

side. This sounds logical as, in the moral reading, the idle one

has to be punished. However, Plates 2 and 3 revert this situation.

The fetters are on Goodchild's side in the church when the mace

is on Idle's side in the churchyard. The position of these two elements

is going to vary all along the series. Thus, these symbols that,

at first sight, seem to be clear signs of success or failure are

in fact hints that suggest another reading. The ambiguities of the

series are already beginning to take shape. However, for the first

time, the opposition of the two characters and the choice they have

made concerning their lives appears clearly. The message for the

apprentices is also very clear.

Of course, this series is a

"moral series" by means of which Hogarth aims at giving

certain notions or lessons of morality to a certain category of

people. Nonetheless, the fact is that there is another dimension

to it, a more universal moral meaning in the sense that most of

Hogarth's contemporaries could take the lesson for themselves even

if they were not apprentices. In James Boswell's, Life of Johnson,

an interesting allusion to this particular fact can be found. It

is certainly made with humour but indeed, it shows us how the images

used by Hogarth had this power to pervade one's mind and to remain

imprinted there:

One

sunday, when the weather was very fine, Beauclerk enticed him, insensibly,

to saunter about all the morning. They went into a churchyard, at

the time of divine service, and Johnson laid himself at his ease

upon one of the tombstones. "Now, Sir, (said Beauclerk) you

are like Hogarth's Idle Apprentice."

Anyway the character

of Idle is, in a way, associated to evil as he is called "the

bad 'prentice" by Hogarth himself. Thus, we now have a kind

of manichean opposition between Good (child) and bad which will

become even stronger in the following plates.

The story

goes on with Plates 4 and 5. Now, we can see that Goodchild is climbing

up the social ladder little by little. He is not working on the

loom any more but is helping his master whose "Favourite"

he is, being "entrusted" by him with the management of

the small silk factory. If we look at the background of the print

we can see that the tiny workshop of Plate 1, where only two looms were installed, has

developed into something much bigger. Now, in the room that the

two men are overseeing, and to which West is pointing at, there

are two women spinning and four - possibly five - others weaving.

Now Goodchild has the keys of the cupboard where he can find the

"day book" that he is holding. It is probably the factory

ledger as Hogarth has provided the young man with a money-bag. Hogarth

has also placed a symbolic pair of gloves that seem to be shaking

hands, thus stressing the perfect understanding between Goodchild

and his master and a partnership yet to come - an understanding

that could already be seen through the posture of Mr West. On the

left-hand side, a porter bearing the arms of the City of London

is carrying four rolls of cloth. This last detail shows that West's

business is productive and probably prosperous... A good prospect

for Goodchild whose social improvement is shown graphically by the

kind of platform he is standing on.

Of course, while life

is getting better and better for the one, it's the contrary for

the other. On Plate 5

Tom Idle is "turned away and sent to sea" accompanied

to the ship by his weeping mother. His indenture can be seen floating

near the boat. There is no turning back possible for him. He is

heading now with all his possessions in his chest to a ship that

is waiting on the shore of Cuckold's point, a reach of the Thames

between Limehouse and Greenwich reaches. One of the men who is also

in the boat is pointing, with a kind of sadistic little grin, at

something in the distance. At first glance, it seems that he is

showing Idle the ship he's being sent to. But, in the direct line

of his finger, a gibbet can be seen on the shore of the reach. It

is another sign foreshadowing Idle's gloomy end. Still toying with

the signs on the printed frame, Hogarth has now moved the ropes

into the story proper. They can be seen hanging from the boat near

Idle who is being tormented by another man dangling a cat-o'-nine

tails, a sort of whip, thus sadistically showing Tom all the sufferings

that are awaiting him on the ship. He is probably sent to the plantations

of Virginia like Moll Flanders. It seems that corporal punishment

is pursuing poor Idle. On Plate 1, there is the master who is about to give him the cane.

On Plate 3, the churchwarden

is ready to hit him with a stick, and now this man is waving a whip

at him. All is there, the violence is not depicted but implied which

is even worse as it leaves it all to the imagination of those who

look at the prints. Most apprentices certainly knew what being given

the cane felt like, as masters used this instrument of correction

frequently. Therefore, Hogarth's drama must have been even more

powerful to them as they certainly did not enjoy the perspective

of a life associated to this kind of physical pain.

The

story continues with Plate 6. Goodchild is now "out of his time", meaning

that he has finished his apprenticeship and, as a "reward"

to this, he has married his master's daughter. The partnership foreseen

on Plate 4 is now

effective. It can be seen on the sign "Goodchild and West"

- the order of the name on the sign shows that Goodchild's status

within the factory has increased significantly. Goodchild and his

wife are at the window, still wearing their night dresses as the

sun has just risen, illuminating the different characters. The couple

is drinking tea which, at that time, was a sign of wealth. Hogarth

has even stressed Goodchild's good manners by really insisting on

his erect little finger. The good apprentice is paying the musicians

who have played a serenade for the newly wed couple outside the

house. The custom was that butchers performed that function so that

Hogarth has placed two of them in the print; they can easily be

recognised as they are holding bones. Hogarth seems to have placed

a device of derision here by showing two members of the orchestra

having an argument. During the eighteenth century it was the tradition

for a wealthy couple to give what was left of the wedding banquet

to the poor. And indeed, that's exactly what they are doing, a servant

is putting some food in the apron of a woman who is kneeling, on

the door steps, with her baby on her back. On the left, there is

a legless beggar who has a ballad called "Jesse or the Happy

Pair. A New Song" to sell.

Life, of course, has not

been so kind to Idle. He has now returned from the sea, and we find

him "in a Garret with a common Prostitute". The girl is

examining an earring. The other one lies on her lap with two watches

and their chains. It is probably the small loot of Tom. On the floor

can be seen alcohol and tobacco, the attributes given to Idle in

plate one. But, most of all, and showing how low he has fallen,

there are two pistols ready. This last detail added to the two planks

that keep the door tightly closed, added to a lock and two bolts,

is a clue telling us that Tom has probably made a few enemies after

he has returned from the sea, and that constables are looking for

him. His face and posture show that he has been terribly frightened

by the cat which is seen falling down from the chimney, dislodging

some bricks on its way, trying to chase the rat that is escaping

on the left-hand side of the print. Idle is tense, anxious. He is

the rat trying to keep away from the cat. Actually, the cat seems

to be a recurring element of the series. It appears on Plate 1, where it is sharpening its claws on Idle's

loom. It's here again on Plate 4, bristling at the sight of the dog, and one last time

on Plate 7. The first

appearance of this emblematic character may be linked to the story

of Dick Whittington - Goodchild's model - whose fortune has been

made thanks to his cat. This means that the cat is associated to

the industrious apprentice in a way that cannot really be explained

at the moment, though it is later to make sense in the parallel

story of the two characters. Anyway, this plate is probably a fairly

accurate description of the conditions under which many of Hogarth's

contemporaries had to live. Indeed, the room is in an awful condition:

the plaster is dropping off the walls and ceiling, there are gaping

holes in the floor which can remind us of the open grave on Plate 3 and once again tell the reader that Hell

is not very far from Idle... The bed has lost its wood work at the

foot and slopes to the ground. This detail is very interesting as

it leads us to realise that there is more than mere fright in Idle's

posture. Indeed, the way he is sitting up on the bed can be interpreted

in another way, leading us implicitly to follow the direction of

Idle's fate.

Hogarth's Drawings, Avalon Press,1948 |

|

(Figure 1)

As a matter-of-fact,

in the original drawing (Figure 1), Hogarth had made Idle look in

the reader's direction, and his hands were not at all in the same

position. But, on the print the artist has moved Idle's face to

a three-quarter position, and the position of the hands gives this

effect of Tom sliding down to a place that frightens him and so,

he is trying to refrain this fall by placing his hands forward.

Therefore, this device used by Hogarth tells the reader that Tom's

fall is not finished yet .

Goodchild's train of success

is not bound to stop either. On Plate 8, he has now "grown rich" and is

"Sheriff of London", an office which was largely ceremonial.

The scene is taking place in what supposedly is old Fish mongers'

Hall, where an enormous feast is being held. Francis is sitting

in the background, under a painting of William II . On the right-hand

side of the print stands a crowd of sightseers and petitioners whom

Hogarth has somehow enframed, and an officer who is holding a mace

and a piece of paper which is a petition for Goodchild. On this

paper the following words can be read: "To the Worshipful Goodchild

Sheriff of London". This could be the end of the story for

Goodchild, his ultimate promotion. But we must not forget that Dick

Whittington is Francis' model. Moreover, Hogarth has introduced

a sign telling the reader that the boy who once was apprenticed

to a master weaver has not yet finished his social advancement.

This hint is the statue that is situated between the windows (Figure

2). Indeed, the character who is immortalised there is Sir William

Walworth, who was Lord Mayor of London during the fourteenth century.

(figure 2)

This character

is especially known as being the one who wounded Wat Tyler - the

leader of the Kentish rebels in the Peasants' Revolt of 1381 - in

a scuffle during a meeting with Richard II, and then had him beheaded.

What is particularly interesting is that Walworth started as a London

salt-merchant who became wealthy and was elected Sheriff of London

in 1370. Four years later, he began his first term as Mayor... Anyhow,

if we look closer to Goodchild and his wife, something is quite

striking. As opposed to the front characters, Goodchild seems to

remain very sober and composed, the couple even seems isolated.

We are facing a paradoxical situation as we would expect Goodchild

to enjoy his new position fully , but on the contrary he almost

seems to be bored...

Meanwhile, Idle is again behaving

wrongly "in a Night-Cellar" , where a fight is taking

place, "with his Accomplice" (the accomplice being the

same man, with the eye-patch and stripped hat, Tom was gambling

with on Plate 3 when he

should have been at church). A man on the right is getting rid of

a dead body with a bullet hole in the chest and blood flowing from

it. We can assume that Idle is the killer, or has played an important

part in the murder, as he has a pistol in his pocket - and another

one lying at his feet - and that he is sharing what were probably

the possessions of their victim with his accomplice. The girl he

was in a garret with on Plate 7 has betrayed him. She is pointing at him while taking

a coin from a constable who enters into the cellar in order to arrest

Idle. His prospects are getting worse and worse and Hogarth has

once again moved the hangman's noose into the print. Now, it is

hanging from the ceiling in the background.

These two Plates,

8 and 9, are really interesting in terms of space as they clash

with the preceding ones. As a matter-of-fact, if we look more carefully

at Plate 8, there

is something that strikes the eye immediately. Hogarth has placed

Goodchild so far in the background that we can only distinguish

his figure and assume who he is. Instead, more or less on the left

of the print, we are facing a lot of disgusting, ugly, members of

the City establishment who are gobbling up their food as if they

had not eaten for weeks. What is worth noticing is that if we look

back at Goodchild's life and thus move backwards to Plate 6, on the left we have this horrible crippled

beggar. On Plate 4,

still on the left , there is the porter with his ridiculous, enormous

nose. On Plate 2, on the

left again, there is this witch-like old woman, the pew-opener.

We can thus notice that Hogarth has placed all these ugly, negative

characters on the left of the print. Hence Goodchild has to be either

at the centre or on the right. And indeed, if we look again at the

different prints, we can definitely see that from Plate 1 to Plate 6, he is always situated on the right. On Plate 8, he is situated in the centre. What about

Tom Idle? on Plate 9,

he is more or less in the centre of the plate. But in the preceding

ones, he always appears on the left: in the workshop, in the church-yard,

on the boat, in the garret. What is interesting is that in Idle's

story there is, apparently, no significant character on the right

of the prints. This leads to the question of the role of these left-hand

side characters that can be found in the even number plates. Ronald

Paulson - in Emblem and Expressions - has come up with an explanation.

He calls these characters "repoussoir figures" and according

to him, their function is to "stabilize the composition"

and to lead "the viewer's eye into it, establishing its depth

(...) The viewer's habit of left-right association with Idle and

Goodchild leads him (...) to see the left-hand figure as another

denizen of Idle's gross world, which Goodchild cannot escape even

in the safety of the counting house, and the contention between

these worlds is an aesthetic one now of beauty vs. ugliness".

However, Idle's world is not totally absent from the preoccupations

of Goodchild. This is when the cat plays its part. Indeed, on Plate1,

the cat seems to be harassing Idle, and it is here again running

after the rat on Plate 7.

Goodchild, being associated with the cat, seems to be the one who

is going to end up with the power. But Hogarth is also telling the

reader that, whatever direction the two boys are taking, they are

linked in a particular manner. Something of Idle is always here,

facing Goodchild while something of Goodchild keeps tormenting Idle.

Plate 10

is the second and last time that Idle and Goodchild can be seen

together. As it is said in the title of the plate, the industrious

apprentice has become alderman of London. Idle - who is wearing

manacles - is begging Goodchild for mercy, but the latter sits with

his head turned away from the repentant law-breaker and is hiding

his face with his left hand. Apparently, Goodchild is having pangs

of conscience for having to sentence Idle to death. On Goodchild's

right, a clerk is sitting at a desk and is writing down the evidence

on a piece of paper that he has probably taken in the open drawer.

On the paper can be read the following sentence: "to the turnkey

of Newgate", the famous jail where Idle is probably going to

spend some time before the execution takes place. On Idle's left

his accomplice is standing, the one we have already met on Plate 3 and Plate 9. He is easily recognisable because of his

striped cap and his eye-patch. He is swearing the oath falsely while

the official who is holding the Bible is taking a bribe from a woman

who is standing behind him. On the right, just behind Goodchild,

stands Idle's mother who is weeping and talking to a stout beadle

who is holding a staff of office. This staff doesn't seem to have

been placed here with no particular intention. On the contrary,

there is a sharp opposition between the stiffness of this pole and

the poor Idle who is crouching in supplication. Hogarth may have

used this device in order to stress Idle's posture. However, it

seems that the beadle's staff has another purpose, as it is in fact

cutting the composition into two parts. On one side, there is the

woman who is giving a bribe, an official eagerly accepting it, the

accomplice turned King's Evidence who is sending Idle to Newgate

and then worse, and closer to the centre is the begging Idle. Thus

there are four main characters on the left of the plate. On the

right of the pole, stands the beadle who seems to tell the crying

mother that nothing can be done to save her son, then comes Goodchild

and the clerk. Again, there are four characters. Hogarth has then

added different characters, forming a crowd. The features of some

of them can be figured out, others are just vague shadows establishing

a link between the two sides of the print. Indeed, the whole effect

of the staff, cutting the print into two with an equal number of

characters on each side, is one of careful balance in the composition.

This balance suggests that Hogarth, though he has finally made Idle

and Goodchild meet in this City court room, keeps a kind of separation

between the two characters, as if he tried not to break the rhythm

installed little by little by means of the painting of the preceding

plates. In a way, he is trying to keep the same system of balance

and binary opposition that he has used up to this stage of the story.

However, if we are looking at the different parts separately, it

is possible to notice that a direct causality chain is created between

the two sides. As a matter-of-fact, on the left, the woman is bribing

the official who then allows the accomplice to make a false oath,

the accomplice thus sending Idle to Newgate. On the right the beadle

is saying "no" to Idle's mother who is crying. Goodchild,

looks as if he does not want to see, does not want to hear, but

has to carry out what his function compels him to do. The final

result is the clerk writing the note. But, even though it seems

that Hogarth has created two parallel prints fused in one, he has

also created a subtle causality chain that once again balances the

whole print and gives it its completeness by linking the two sections.

Once again, we can start from the woman who is giving the coin to

the official who is closing his eyes on the accomplice's perjury.

At that particular point, a small detail added in the engraving,

can be seen linking the back of the accomplice to that of Idle's.

Emerging from the crowd there is a small hand whose owner cannot

be seen. This hand is pointing a finger accusingly at Idle, who

is done for. If we draw a line through the print, following the

axis of the finger, we would move from the accomplice to the pointing

finger to Idle's hands joined in supplication, then to Goodchild's

heart whose chest is massive and stiff - contrarily to Idle - and

then to the hands of the clerk writing down Idle's sentence. However,

nothing can be done for the idle. A faint feeling of death exhales

from this court room. Sentencing someone to be hanged is common.

There is no redemption possible.

Hogarth has placed all these

fire buckets hanging from the ceiling. Really practical, that's

true. But don't they look like rows of hangman's nooses with the

heads still attached to them ? It really seems, that Hogarth has

here included a slight criticism on the way justice practiced chain

hanging. Anyway, Goodchild's posture seems to show regret, but it

can also be interpreted as symbolic of Blind Justice , as he is

hiding his face - the alderman has to act with equity, and not to

take his own feelings into account - "Thou shall do no unrighteousness

in Judgements", says the caption taken from Leviticus. Ironically

enough, it seems that this is exactly what Goodchild is doing. As

a matter-of-fact, by hiding and turning his face he is prevented

from seeing the bribery that is going on.

Thus, the message

for the apprentices is quite clear. The boy who gets the chance

to be apprenticed, but who lets it go because of idleness and who

finally falls into crime gets what he deserves - and even more.

It is clear, that even though the series is supposed to be simplified

as it is addressed to the uneducated classes, Hogarth is still toying

with criticism of all sorts and in this particular plate, by playing

with the idea of Blind Justice, he has included a harsh attack on

the judicial system that was far from being fair. Roy Porter stresses

this fact : "As legal reformers such as Colquhoun and Jeremy

Bentham insisted, laws indiscriminately prescribing execution for

murder and for lifting handkerchiefs were unlikely to hinder heinous

crime [...] In the London area so called "trading justices"

having bought their offices, milked them through fees and bribes".

Horace Walpole himself declared "the greatest criminals of

this town are the officers of Justice" . This might bring a

little nuance on Goodchild's apparently positive success.

The story

then reaches Plates 11 and 12. The first thing to notice is that

the order that Hogarth has followed all along the story is reversed.

Idle is the first one on the scene. Hanging from the printed frame,

no more ropes or fetters but two skeletons. He is now going to be

"Executed at Tyburn" in front of a massive crowd. The

gallows - which, funnily enough, look exactly like the looms of

Plate 1 - can be

seen on the right in the background - they were usually called the

"triple tree of Tyburn" because of the three horizontal

beams that could hang eight men at once each - and lying on one

of the beams is the hangman, the "King of Tyburn", who

is calmly waiting to carry out his sad function, while casually

smoking a pipe. It is interesting to notice, that most executioners

were men of low mentality who often ended on the gallows themselves.

In the centre of the print, in the background, can be seen the "Ordinary

of Newgate" who is addressing the crowd from his coach fulfilling

once again the wish of Robert Dow, a merchant of London who, at

his death in 1612, left an annuity of £1 6s. 8d, to ensure

the spiritual exhortation of those who were going to be executed.

A man, crouching on top of the cart, is trying to remove the Ordinary's

wig with the help of a stick. Followed by a troop of mounted soldiers

holding spears, Idle is arriving on the scene, praying out of a

book, sitting in an open cart next to a Methodist minister who is

exhorting him to repent. The poor boy is lying against his own coffin

and looks exhausted, as if his health has been severely damaged.

This is probably due to the time he has spent in Newgate prison.

Actually, Idle has probably just taken his last drink at St Sepulchre's

Church where it was traditional to lead the prisoners who had to

go out of Newgate's prison at 9 a.m. in front of a huge crowd which

was waiting to hear the bell toll and see them get into the cart.

The criminals were then put back into the cart and led to Tyburn,

followed by a procession of spectators. In 1783, an end was put

to the traditional executions at Tyburn. Criminals were, from that

year on, hanged within the walls of Newgate, protected from the

confusion caused by such a great number of spectators. This decision

was taken much to the discontent of many as we can read in James

Boswell's Life of Johnson:

The

age is running mad after innovation; all the business of the world

is to be done in a new way; men are to be hanged in a new way; Tyburn

itself is not safe from the fury of innovation.[...] they object

that the old method drew together a number of spectators. Sir, executions

are intended to draw spectators. If they do not draw spectators

they don't answer their purpose. The old method was most satisfactory

to all parties; the publick was gratified by a procession; the criminal

was supported by it. Why is all this to be swept away ?

This extract shows how

important Tyburn was in the popular tradition. Thus, when Idle arrives

at Tyburn, the crowd that is awaiting him is already massive, and

there are many details showing how lively it is. On the right-hand

side, there is a structure much like a grandstand where those who

wished to have a better view of the spectacle could stand, but is

was reserved for people of fashion as we can figure out from the

print. On the right-hand side of the foreground there is a cart

where some women are standing and selling gin probably. On the extreme

right-hand side can be seen Idle's mother who is, as usual, crying

in her apron. Close to the cart, there is first a group of men armed

with sticks who are busy beating someone or something. Then, there

is a little boy who has just overturned a wheelbarrow filled with

apples and who is, for this reason, being punched in the face by

the woman who was pushing it. The next character, in the immediate

foreground, is called Ford but was very famous and popularly called

"Tiddy Doll" . His presence here is not surprising at

all. He was a famous ginger-bread seller, quite eccentric who was

always hailed as the king of itinerant tradesmen. He was very well

known for being a constant attendant in the crowd on Lord Mayor's

day. However, Hogarth has not placed him in the crowd of Plate 12. He was also regularly attending the executions

at Tyburn and the May Fair. He liked to dress like a person of fashion.

On the plate, he can be seen wearing his nice clothes, holding up

a ginger-bread cake with his left hand, the right one being in his

coat, Napoleon-like, and haranguing the crowd to gain customers.

A man can be seen, holding a dog by the tail, as if it was a potato

sack, and about to throw it at Idle's face. Cruelty and ill treatments

to animals were very common things at that time, and this is one

of the things Hogarth stood against, for instance in his famous

series The Four Stages of Cruelty. He dedicated his artistic talent

to attract the attention of the population and to raise the problem

of such terrible behaviour to animals. In the centre of the print,

a woman with a baby in her arms is holding "The Last dying

speech & Confession of Tho. Idle". It was traditional in

the eighteenth century that before being executed, a criminal would

write his "dying speech", usually telling the reader about

his life of sins, explaining his regrets, and recommending others

not to make the same mistakes as he did. However, it is important

to note that these criminal confessions were usually fabricated

by hacks for booksellers - very few, if any, were genuine. Following,

is an extract taken from the dying speech of John Selman , who was

executed in 1612 :

The Dying Speech of

John Selman

at his place of execution, Charing Cross, on 7 January

1612

I

am come (as you see) patiently to offer vp the sweet, and deare

sacrifice of my life, a life, which I haue gracelessely abused,

and by the vnruly course thereof, made my death a scandall to my

kindred and aquaintance: I haue consumed fortunes gifts in riotous

companies, wasted my good name in the purchase of goods vnlawfully

gotten, and now ending my daies in too late repentance, I am placed

in the rancke of reprobates, which the rusty canker of time must

needs turne to obliuion. I stand here as shames example, ready to

bee spewed out of the Common wealth. I confesse, I haue knowne too

much, performed more, but consented to most: I haue bin the only

corruption of many ripe witted youth, and leader of them to confusion.

Pardon me God, for that is now a burthen to my conscience, wash

it away sweet Creator, that I may spotlesse enter into thy glorious

kingdome. Whereupon being demanded, if he would discouer any of

his fraternity, for the good of the Common wealth or not: Answered,

that he had already left the names of diuers notorious malefactors

in writing behind him, which hee thought sufficient. So hee requested

the quietnes of conscience that his soule might depart without molestation.

For (quoth he) I haue deserued death long before this time, and

deseruedly now I suffer death. The offence I dye for, was high presumption,

a fact done euen in the Kings Maiesties presence, euen in the Church

of God, in the time of diuine Seruice, and the celebration of the

Sacred Communion, for which if forgiuenes may descend from Gods

tribunall Throne, with penitence of hart I desire it, all which

being spoken, he patiently left this world for another life. But

see the gracelesse and vnrepenting minds of such like kinde of liuers:

for, one of his quality (a picke pocket, I meane) euen at his execution,

grew master of a true mans purse, who being presently taken, was

imprisoned, and is like the next sessions to wander the long voiage

after his grand Captaine, Mounsier John Selman, God if it bee his

blessed will turne their hearts, and make them all honest men...

FINIS

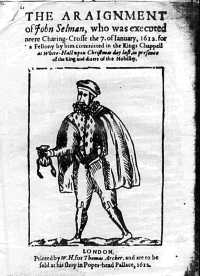

(Figure 3) |

THE ARRAIGNMENT / of John Selman, who was executed / neere Charing-Crosse the 7. of January, 1612. for / a Fellony by him committed in the Kings Chappell / at White-Hall vpon Christmas day last, in presence / of the King and diuers or the Nobility. / [woodcut of John Selman holding a purse, 13.5 cm. x 18 cm.] / LONDON. / Printed by W.H. for Thomas Archer, and are to be / sold at his shop in Popes-head Pallace,1612 |

These dying

speeches usually had tremendous success with the population. Even

if John Selman's one (Figure 3) is dated more than a century before

Hogarth actually created Industry and Idleness, it is more than

probable that Idle's dying speech is much alike. In it, there are

surely words like those used by John Selman, words talking about

abuse, unruly life, confession and repentance. Idle knows that what

is waiting for him is definitely not a nice experience as death

was not immediate usually and the strangulation by the rope's knot

was, in fact, a slow process. Some criminals have been hanging for

quite a long time without dying. But the immediate after life, for

hanged men, was not a very exciting prospect either. Indeed, the

College of Surgeons that was then at the Old Bailey, was entitled

to all bodies coming from Tyburn to use for dissection experiments.

The character which is being examined on the plate ironically entitled

The Reward of Cruelty (1751) could well have been Tom Idle. In order

for the body to be put in the ground, the family or friends would

have had to buy it - actually it was quite common for the close

relatives to buy the criminal's body, not for a religious purpose

but in the hope of being able to revive him, as the painful strangulation

was not always conclusive.

On the left of the speech seller,

a woman is punching a man who has fallen down on the ground, on

a baby. The man was probably flirting with the third woman who is

holding a basket and showing the palm of her hands in a movement

of surprise and helplessness. However, this is also very demonstrative

of the little care that was taken of children at that time. Actually,

this becomes a recurrent theme in Hogarth's work. The same carelessness

can be found on the print entitled Gin Lane (1751), with the mother

who is letting her child fall from her lap. Actually, it is possible

to notice that Hogarth has insisted on the presence of new born

children. Thus, there is the one lying on the ground on the foreground,

a baby's face can be noticed emerging from the shadowy crowd, another

one can be seen on the right-hand side, in the cart, and one more

in the speech seller’s lap. Their presence at Idle's execution is

not due to the cruelty of parents who did not care about showing

the spectacle of death to their offspring. On the contrary, it was

a very common tradition that women would bring their babies to an

execution at Tyburn, the popular belief being that touching the

head of a new born child with the hand of a hanged man would protect

it from all sorts of illnesses. On the left of Plate 11, there is a soldier who is kneeling because

he is caught in the mud. Two boys on the extreme left of the print

are looking at him, laughing. Once again, Hogarth has inserted a

typical image of what usually happened during executions at Tyburn.

Indeed, public hangings were meant as a warning for the population.

But this warning was hardly taken into account, and during spectacles

such as the ones that took place at Tyburn, pick-pockets were busy

in the crowd.

Then arrives Goodchild on Plate 12. The horns of plenty engraved on the left

and right of the printed frame, as opposed to the skeletons on Plate 11, show that the subject of this plate is

success. Indeed, the industrious apprentice has become Lord-Mayor

of London, he has reached the position he was aiming at and is now

inside a state coach, on his way to the Guildhall. At the coach-window,

a man with a fur cap and his face barely visible because buried

inside a top hat which seems a bit too big for his head, is holding

the City Sword that has appeared all along the story on the printed

frame. This man is the Marshall of the City. Behind him, at the

opposite window can be seen the silhouette of the City mace, also

a recurrent element on the printed frames. Goodchild is hardly visible

inside the coach.

Around the coach, the crowd is very active,

and there is a sharp contrast between the quiet, organised and peaceful

settings that we have had all along Goodchild's story until now.

Actually, both type of settings seem to have mixed together. Thus,

there are the straight, symmetrical and solid lines of the background

buildings facing the apparent fragility of the wooden grandstands

erected by the London guilds, on the left and on the right. The

procession, which usually took place on November 9 is enormous,

but a few characters manage to stand out from the rest of the crowd.

Thus, on the right-hand side, there is a dwarf holding a scarcely

readable piece of paper on which the following words are written

" A Full and True Account of Ye Ghost of Thos Idle, Which....

It was a popular belief that those who had been hanged would, sometimes,

come back from the dead to punish those who had done them wrongs

during their life. But these stories were also a good way for booksellers

to make some money. In the foreground, a bench made of a wooden

plank lying on two barrels has just collapsed. A chimney-sweep finds

this scene very amusing. On the right-hand side, on the balcony

just above the grandstand made for the commoners, stand members

of the nobility. The hierarchy is thus respected. Among them, on

the left, there is Frederick Prince of Wales who is looking at the

procession and probably also at the sign of the King's Head Tavern

which appears just in the centre of the perspective between the

buildings. The king may not be here physically, but the sign, far

above the common citizens, shows that he is here symbolically. On

the left-hand side, a soldier is leaning completely drunk against

a pole. On his left, a boy looking up a woman's skirt. This woman,

seems to be scratching the face of the man who is kissing her.

PART II

Inversion and Paradoxes : the hidden discourse of Industry and Idleness |

The story

of our two apprentices can also been studied on a different level

which puts aside the direct pedagogical aspect of the series and

tells us more about Hogarth himself - an alternative reading which

subverts the whole system of values the prints seem to put forward.

Indeed, we suggest an analysis of Hogarth's plates which can be

applied to other works of his. For instance, the two contrasting

plates Gin Lane and Beer Street created by the artist in 1751 suggest

a similar line of study. Indeed, this was quite often the case with

Hogarth's work, and this was probably playing an important part

in his creating power: the apparent positive values illustrated

on a print can be reversed just by looking a bit more carefully

at the plates, and deeper into the details. The reversal of these

positive values is not meant to describe them as entirely negative,

but to bring forward a kind of nuance, which often looks paradoxical,

in the values of the period.

1.Transgression: the hidden significance of Industry and Idleness

As we have

seen, Goodchild's ultimate advancement is something that very rarely

happened in reality. However, it is quite often that apprentices

took their master's business and then married their daughters. It

happened to Samuel Richardson, the author of Pamela (1739)

and this is also exactly what happened to the "apprentice"

William Hogarth who was taking painting lessons and studying the

Old Master's art in an academy created by the painter James Thornhill.

Eventually, Hogarth married Thornhill's daughter and even became

more successful, more famous than his master - Hogarth is often

referred to now as the father of British art. The fact is that the

author's story is very similar to that of Francis Goodchild as Hogarth's

story is one of rags to riches as well. But, a very important detail

in the series brings forward a sort of ambiguous situation... Let

us have a look at some of Hogarth's self-portraits - Hogarth Painting the Comic Muse (1758) or Gulielmus

Hogarth (1749) for instance

- or one of his paintings called Calais

Gate, or The Roast Beef of Old England (1748) where a "spy" taking notes can be spotted

on the left-hand side. Actually, this character is Hogarth himself

who has included himself in the work because, during a trip to France,

he had been arrested on suspicion of spying whereas he was just

making sketches. Now, if we look at Idle's face, especially in the

churchyard or in the Garrett, there is only one conclusion that

can be reached: Though his life coincides with that of Goodchild,

Hogarth has given his features to Idle.

|

|

|

(Figure 4)

On these close-ups (Figure 4), we can see that Idle's line of the

nose, of the chin, of the lips of the eyebrow is completely identical

to that of Hogarth's likeness in Calais Gate and on his self-portrait,

even though the idle apprentice's curly hair is entirely his own...

Many different

explanations have been given concerning this observation. Some even

say that he may have done it unconsciously, hence projecting some

of his hidden desires onto the paper : "Whether for purposes

of self-irony to balance the saccharine self-portrait of Goodchild,

or at some less conscious level, Hogarth has introduced his opposite...

Psychologically, this may be described as the tendency of the mind

to react defensively against what another part of it is reacting

toward..." . This proposition has to be qualified. He may have

done so as a way to say "yes" to what he usually said

"no" to, but the theory which says that Hogarth has "on

a less conscious level" applied himself to draw this fictitious

character, giving it his own features... this seems a bit far-fetched.

Actually, many theories or interpretation can be suggested.

For instance, as seen in the iconological analysis, Hogarth has

inserted a "repoussoir figure" within each plate of Goodchild's

story which is supposed to tell or maybe to recall the apprentice

that even if his situation is improving everyday, sufferings are

never very far from him and probably keeping an eye on him. However,

the study also demonstrated that, apparently, there were no equivalents

to these figures in Idle's story i.e. that, apparently, no reminders

of Goodchild's seemingly well ordered world can be found facing

the idle apprentice. This last assumption can be brought down with

an interpretation saying that, by giving Idle his own features,

Hogarth gives the "bad apprentice" the dimension of a

figure of hope as Hogarth has definitely been a successful idle

himself. According to his autobiographical notes, the words "idle"

and "idleness" could well have been applied to him at

the time when he was apprenticed to a master silver engraver. Of

course, Idle can be described as a figure of hope if one takes one

specific aspect of his destiny into account. Indeed, at that time,

having the possibility of being an apprentice was a real privilege

because it meant survival. In fact, some London parishes admitted

that "no infant had lived to be apprenticed from their workhouses"

and even though many actions were taken by different charity organisations

to put a stop to this situation, no really efficient solutions were

found. Thus, when Jonas Hanway, a merchant and a philanthropist

who took part in the development of the Foundling Hospital and other

charity institutions, went into the different parishes (fourteen

altogether at that time) in order to enquire about the welfare of

infants, he discovered abominations such as the terrible infant

death rate in the Parish of St Martin-in-the-fields which showed

that out of the 1200 babies born every year, 900 would die because

of the carelessness of the women in charge who were euphemistically

called "nurses". All in all, Hanway estimated that the

infant death rate within the workhouses set up since 1720 was around

88%. The reason why Idle can, in a way, be considered as a figure

of hope then becomes quite obvious...

The projection of his

own persona into his work can also mean that Hogarth was basically

trying to tell us, and especially the apprentices who might have

had a glimpse of this hidden meaning, "Look at what could have

happened to me!" (and therefore, at what could happen to you!).

In that case, he is still sticking to the intended moral meaning

of Industry and Idleness which then links Idle's character directly

to its purpose in the iconological analysis. However, this interpretation

is most unlikely, only because Hogarth was no orphan or parish child.

But let us suppose that, even if he was trying to simplify the meaning

as much as he could, Hogarth has added something deeper and was

trying to attract the reader's attention on this particular character

and at the same time to live what his character is living. Why should

he have done such a thing? After all, Idle seems to be living a

life that leads him directly to death. His fate doesn't appear to

be very enviable compared to that of Goodchild. To find possible

answers to that question, we have to move back to Idle's story and

see how easy it is for him to forget all the taboos, to put aside

all the established laws and rules, it seems that Hogarth, through

his projection, is definitely trying to get a taste of it all. An

interesting point to notice is that the author is, on the one hand,

advocating church attendance through the character of Goodchild

who is "performing the duty of a Christian" and on the

other hand he seems to have this strong desire to be unfaithful

to the Ten Commandments, given by God in Exodus, through his own

incarnation of Idle . As a matter-of-fact, all along Idle's story,

most laws imposed by God through the Ten Commandments are broken.

For instance, God says "Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it

holy." [Ex 20:8] but on this day, Idle is gambling. He also

says "Honour thy father and thy mother..." [Ex 20:12],

but Tom's mother is dishonoured and she cries because of her son's

behaviour. "Thou shall not kill" [Ex 20:13] and Idle has

just killed someone on Plate 9 in order to rob his victim : "Thou shall not steal,"

the commandment says [Ex 20:15]. We can also easily imagine that

he has taken "the name of the Lord [...] in vain." [Ex

20:7] several times. He also has, without any possible doubt, broken

the commandment "Six days shalt thou labour, and do all thy

work:" [Ex 20:9]. Thus, apparently, Hogarth has placed the

reader in front of a paradoxical situation by implying "that's

what is supposed to be good but that's what I wish I could do".

As a matter-of-fact, Hogarth's aim with Industry and Idleness was

to moralise, but by digging further down under the superficial meaning,

and by putting aside what meets the eye so easily, these positive

moralising values seem to be reversed by the author himself.

2.Death in Life, Life in Death

I have asked

myself which character I like best in this series. The answer for

me is obviously Tom Idle, but why should it be so, as he appears

to be the bad character of the story? It is usually said that the

interesting character is always the bad one (in films, books etc...).

Maybe it is so, but the fact is that on looking at Idle's life and

then at Goodchild's the choice is quickly made. When Goodchild is

living like an Arcadian shepherd with an easy, quiet but boring

life, Idle is the one who is alive, who experiences sufferings,

anxiety, pleasure, fright, greed, as a close study of the heroes'

faces can show (Figure 5)...

(Figure 5) : These close-ups

on the two characters' faces allow us to notice the variety of expressions

on Idle's face, one for each plate. On the contrary, there is only

one proper human expression that can be noticed on Goodchild's features...

it's on the last close-up and it's regret.

To sum it up,

Idle experiences proper human feelings and he lives an adventurous

life. Of course, in the end he is hanged at Tyburn but the fact

is that he has chosen to live this risky life, following his model

Moll Flanders. The piece of paper that is stuck on the loom was

interpreted, at first, as a sign of his idleness whereas now, it

can be seen as a sign of his will power to choose and follow a model

that could lead him to his death, and this just for the sake of

living a full human life. However, we know that Moll Flanders, in

the end lives in peace and affluence in Virginia. So, here, the

story of Moll Flanders gives us a hint that Idle's end might not

be as terrible as it seems. Of course, Goodchild also has made a

choice. He is following his ideal, his model Dick Whittington but

because of this, he is living in a world that has replaced the notion

of feelings by that of tradition and calculation. This can be seen

on Goodchild's face, all along his story (Figure 5, p.29). He is

the mirror of constant self-satisfaction appearing through a silly

smile (probably meant, on a superficial level, to seduce the reader),

and the incarnation of sycophancy, of the calculating ambitious.

Is he giving food to the poor out of altruism or just because it

is the custom to do so? Thus, what seemed to be so evident in the

preliminary study of the series - where we have seen this constant

opposition of "good vs. bad" - is all shaken up and turned

upside-down...

Indeed, Tom Idle is experiencing life through

the constant call of death whereas Goodchild is dead, metaphorically

speaking, before having the least notion of what living means. But,

here again, the plates can be seen from a totally new point of view

and death in Idle's life can take a positive value. Indeed, on Plate 3, Idle is lying on a coffin among a mass

of ominous skulls and bones. The first meaning we have seen was

that Idle had already one foot in the grave because of his behaviour.

However, the simple fact that Hogarth has chosen to place his own

representation on a coffin, playing with these pickpockets, suggests

the idea that Idle is not thinking about his own death or that he

doesn't care. Then, on Plate 10, he is imploring Goodchild not to sentence him to death.

Thus, it seems that he is afraid to die. He was not thinking about

it but now it comes to him, he is afraid. That situation is a normal

human behaviour. So, this notion of death present in Idle's story

emphasises the importance of his life instinct and the fact that

he is free in a world where each liberty is a temptation. On the

contrary, except for the "repoussoir figure" that introduces

a silent feeling of suffering and stress into the seemingly Arcadian

life of Goodchild, there is not the least call of death in the latter's

story. Once again, the values reached in our initial analysis are

reversed. Death which was associated to Idle because he is "bad"

is now associated to him in order to stress his quality as a creature

full of life. In fact, Goodchild seems now to be lacking this notion

of physical death which would have made him more than a fictitious

character supposed to represent hope, it would have made of him

a human being. The effect is that Idle seems to have more of a presence

in the succeeding plates. He is more likely to catch the attention

of the reader, who refuses to let himself be blinded by the explicit

moral discourse of the plates.

3. Openness and confinement: the theme of Liberty

Death being

one of the themes developed in the series, another parallel can

be made with Gin Lane and Beer Street concerning the issue of liberty

in the plates. Liberty, a recurring theme in Hogarth's work, is

often expressed through the depiction of the different settings

in a story. For instance, in the above-mentioned prints, if Gin

Lane seems to be the place where decay and depravity have settled

down, the scenery implicitly tells the reader another story : Beer

Street is more enclosed between massive brick walls, there is no

outward perspective whereas its counterpart is much more open, more

lively. Liberty is all there within Gin Lane, but temptations as

well. This type of study can be applied efficiently to Industry

and Idleness. It can expose before the reader a whole world of temptations

in which Tom Idle is plunged - it may not have been just a coincidence

that Hogarth has chosen Moll Flanders, a woman, as Idle's example

- and, given the fact that Hogarth has supplied this character with

his own features, a world that irremediably attracts the artist

but frightens him at the same time.

Thus, on Plate 1, both Idle and Goodchild seem to be blocked

inside the workshop. However, at that stage, Goodchild seems to

be the one on the open side of the print. He is next to the open

door - even if a dissuasive element is standing in the doorway -

next to the window on the other side of which he could have seen

this world of powerful temptations if he had not been so concentrated

on his loom, if he had not complied with The Prentices' Guide so

blindly. However, Idle who is leaning against the structure of his

loom and soundly dozing has already one foot outside. All these

temptations attract him, the left quarter of his loom has already

disappeared beyond the frame, and he is slowly drifting along with

it. The ghost of Moll Flanders, floating just above his head is

leading him out of the workshop. On Plate 3, he is definitely outside and already caught

in the dangerous spiral of freedom. The churchyard is, of course,

an open place. This is what Hogarth has linked with the notion of

Liberty. However, the coffin, the skulls, the huge hole in the ground

express the artist's fears of all these attractions or maybe the

fear of a world he knew when he was a child and which has left him

with the tough remembrance of a father who was not successful in

his professional ambitions and who finally found himself in the

Fleet prison for debtors. What Idle is, Hogarth is as well. But

what Goodchild needs - we must bear in mind that Goodchild's life

is Hogarth's - Hogarth needs too. And this is probably why on Plate3, it is possible to see the massive outer brick walls

of the church where Goodchild has taken refuge on Plate 2. These walls not being enough of a confined

space to protect the industrious apprentice from the outside world,

the latter is standing behind the wooden structure of the pew, with

the door half closed which, from his perspective, encloses him even

more. On the left, as a reminder of Idle, the pew opener is sitting,

waiting for newcomers, part of her figure outside the frame. Plates

4 and 5 carry on with this idea of an enclosed vs. open opposition.

Here, Goodchild is once again within a totally closed-in space.

This time it is the workshop that protects him. His fear of the

outside world is expressed through the cat which is arching its

back on seeing the dog that is walking in with the cloth porter.

The latter, is coming in from the world of temptations and like

Idle's loom, like the pew opener, he has - more or less - a quarter

of his figure and attributes outside the frame. On Plate 5, Idle could not be in a more open space.

Liberty pervades the whole plate. Every detail is symbolic : the

sea, the vessels about to leave, the wind blowing in their sails

and activating the windmills, the completely clear horizon. Freedom

is all around Idle, all around Hogarth, but it is frightening, it

can be painful and it can lead to death because there is no determined

path to follow, a safe choice is hard to make, and there is no real

possibility to protect yourself. All the characters in the small

boat - and especially the rower who is a bit like Charon, the boatman

of Hades, leading Idle to his death, symbolised by the gibbet on

the shore - become symbols of these suggestions and are here to

tell the reader about the reality of the artist's desire for Liberty

but the fear he has for what it may imply. Goodchild is not willing

to take any risk and therefore hardly gets his arm through the sash-window

on Plate 6. Indeed,

as usual, he is all closed-in within massive brick walls. The horizon

line is blocked by huge buildings, the doorway is completely blocked

by a broad-shouldered servant and the orchestra is creating a sort

of compact enclosure around the entrance of Goodchild's house. The

only hitch to this human wall is the legless beggar, who seems to

break the reliability of the industrious apprentice's shield against

the outside world and the butchers brandishing bones as a kind of

humorous memento mori. Plate 7 is probably the most interesting as regards to this idea

of Liberty and the fear of it. Idle is in the garret, lying in the

bed, absolutely terrified. At first glance, the room seems to be

totally enclosed. Idle should be protected from this world of temptations

but, if we look closer, all sorts of details stand out against the

shadowy room. First of all, we can notice that all the items of

temptation are already in the room with him. The pipe, the gin,

the tobacco and the pistol show that he is about to give way to

vice. Then, we can notice the gaping holes in the floor, the wall

falling into pieces and ready to collapse, the cat falling from

the, therefore, open chimney and taking a few bricks on its way

down, the rat escaping on the left- hand side, probably through

another hole, and the door, closed with three locks and reinforced

by two planks. Idle has freedom, but at the same time, he is afraid

of it. However, for Idle there is no other possibility, everything

is collapsing around him. The cat is trying to get the rat, but

the rat is going to escape.

As the story advances, Goodchild's

space is getting more and more confined. On Plate 8, he is once more protected by massive walls.

Of course, there are windows, but if we look through them, the only

sight we can get is that of trees blocking the perspective. There

is, as usual within the Goodchild plates, the feeling that everything

is in order, tidy, perfectly symmetrical. Here, the square shape

prevails. The windows and their panes are square, the floor is covered

with square tiles, the wall is decorated with square framed paintings

and with rectangle shapes. The long bench is square as well, and

the tables are arranged in a square shape so that Goodchild and

his wife, who are emerging in the background of the plate, look

as if they were part of a low wall made of all the characters eating

around the square shape table. Actually, Goodchild and his wife

look as if they were either part of this low wall or characters

in a portrait, a royal couple for instance, hanging on the room

wall. They seem to be the continuation of the portrait of William

II just above their heads. The funny thing about this print is that

the only real opening there is - the one situated on the right-hand

side and from which a crowd of petitioners is waiting to see the

new Sheriff of London - was drawn by Hogarth with a frame. The effect

produced is that this opening looks like another painting hanging

on the wall, and therefore is not an opening anymore. However, the

main idea that has to be drawn from this print is that Goodchild

and his wife look completely isolated within all these people who

are busy eating around them. Goodchild is enclosed, a prisoner because

he is frightened by the outside world. On Plate 9, Idle is again moving into what seems to

be a totally enclosed world. The ceiling is very low and the perspective

chosen by Hogarth to depict this night cellar gives the impression

that the place is very small indeed. It is very crowded, and there

is a brawl in the back room. A fire is blazing in the hearth of

the chimney which cannot make up for the lack of light, so it must

be very warm and noisy inside. The staircase on the left-hand side

definitely gives the impression that the characters, as well as

the reader, are buried deep underground. All these details, added

to the smell of tobacco, gin and beer, create a really stifling

atmosphere. Actually, this plate is a turning point for this notion

of Liberty - which is associated with Idle - and all the potential

temptations that ensue from it. As a matter of fact, the general

feeling now is that the idle apprentice is trapped. There is a chimney,

but a fire is burning in the hearth. There is a trap door, but it

is blocked by a corpse that is being pushed through it. Idle is

turning his back to the entrance of the cellar which, anyway, is

obstructed by the presence of a few constables armed with sticks.

Idle and his accomplice are examining their loot which is symbolic

of the temptation that has trapped Idle.

When on Plate 10 the two apprentices meet, the clash is very

interesting as both characters are faithful to their previous condition.

As a matter-of-fact, Goodchild is in his closed-in world defined,

in terms of space, by the wall and the wooden barrier which puts

a physical separation between their two worlds. Goodchild is turning

his head aside as if he wanted to prevent himself from being caught

into the spiral of emotions, of temptations. He wants to stay in

his over-protected world - symbolised here by the amazing number

of fire buckets hanging from the balcony in the background - where

Liberty proper has no place. However, if Goodchild seems completely

isolated and remote from the outside world where Idle is standing,

the latter is, as on Plate 9, trapped. He is, of course, standing on the open door

side of the boundary but there is a whole crowd, very lively and

very noisy, packed around him. This crowd seems to form an obstacle

between him and the way out. Moreover, the massive beadle and the

staff he is holding form an impassable wall.

On Plate 11, there is a subtle mixture of this feeling

of Liberty and of the fact that Idle is definitely trapped. As a

matter-of-fact, once again, the idle apprentice has a whole crowd

packed-up around him. On the right-hand side of the plate, a massive

grandstand blocks the perspective. On the left-hand side there is

a very long wall which blocks the perspective as well. However,

even if Idle is trapped between the coffin and the minister something

tells us that Liberty is not that far away. The most obvious thing

to notice is the background. Of course, Idle is moving slowly towards

the gallows but, at the same time, the cart is moving towards the

hills. The horizon line is not as clear as it is on Plate 3 but still, on this plate the hills give

this feeling of quietness, of peace as opposed to the noise and

stifling atmosphere engendered by the massive crowd. On Plate 12, there is as well a massive crowd but in

Goodchild's story, there is not the least nuance to be made. Here,

everything is an hint of his confinement. First of all, the perspective

is, once again, completely blocked by the huge brick buildings.

On the right and on the left-hand sides, grandstands are echoing

what can be seen on Plate 11. A crowd of men brandishing cudgels and sticks has gathered

around the coach in which Goodchild has hidden. As a matter-of-fact,

the new Lord-Mayor of London can hardly be distinguished and is

situated, more than ever, within an enclosed space.

Thus, if

we look at the plates from an iconological point of view, we would

only see two sharply contrasting stories. One of success, that of

Goodchild, and one of failure, that of Idle, of course. However,

when studying prints made by Hogarth, the reader has to keep in

mind that what stands in front of his eyes is not always what it

seems. We have here a perfect example of this. Goodchild is the